Exploratory data analyses

Overview

Exploratory data analyses (EDA) are one of the first steps in any data project. The goal is literally to explore the data; the better you know your data, the better you can work with it. What are the dimensions (rows and columns)? What types of data are there? Does anything need to be re-coded? What is the missingness like? These are the sort of questions we try to figure out during EDA.

Today we will be using the basic plots built into R. They are all pretty ugly, and you probably won’t want to share them anywhere. Don’t worry though, we’ll have two full days later on dedicated to making great looking plots. The simplicity of the basic R functions limits the number of new concepts to learn at once.

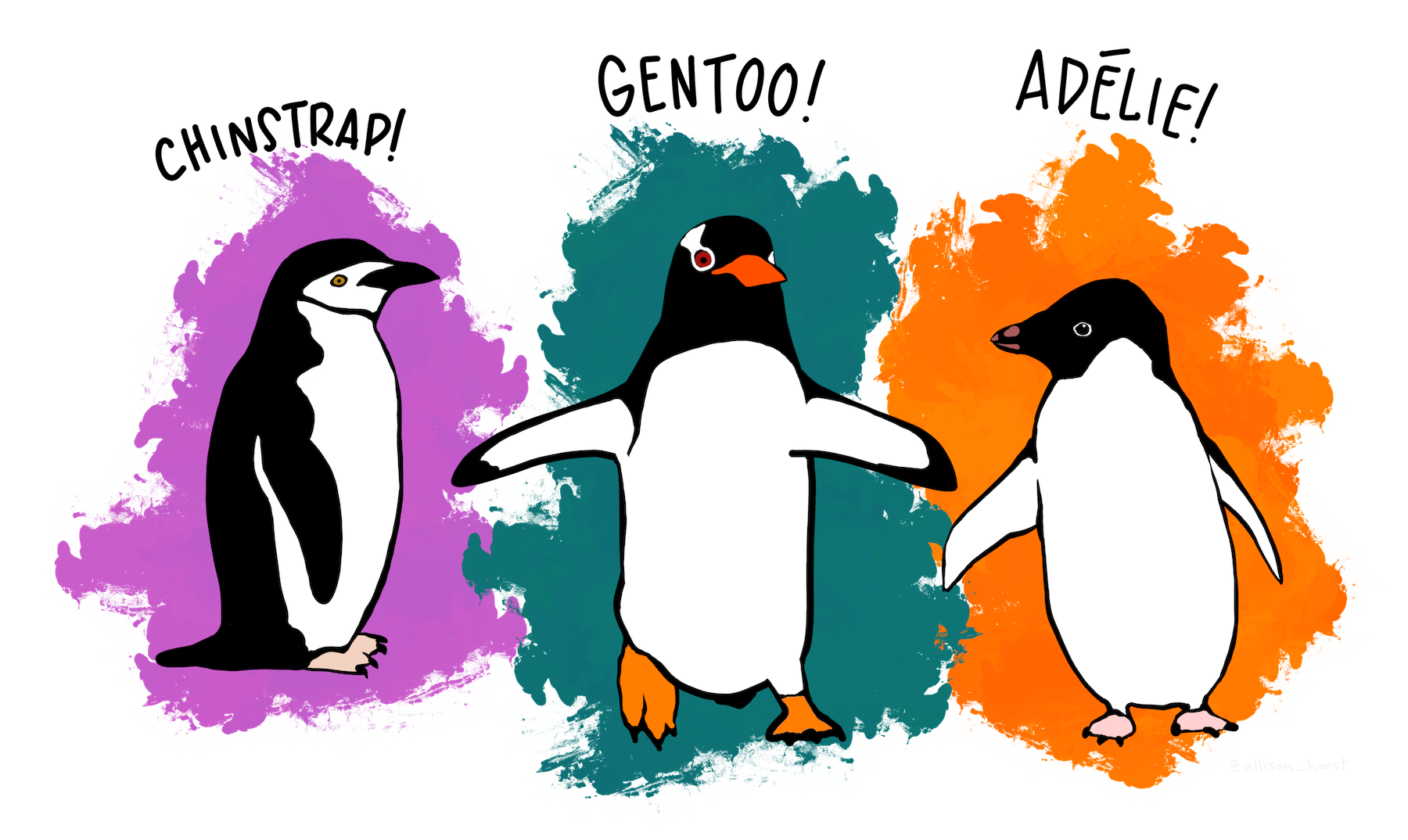

Today we will be looking some biological data, specifically penguins 🐧. The palmerpenguins R package grants easy access to data from Palmer Station in Antarctica, part of the Long-Term Ecological Research program. It contains data on 344 penguins, and aside from being fun, is a great way to learn about data visualization.

Problem Sets

1. Load the Data

First up, we will need to install the palmerpenguins package to get the data, load the package into R, and then put the data into our environment. You can do that with the following commands:

install.packages("palmerpenguins") # To install the data

library(palmerpenguins) # To load the R package

penguins = data.frame(penguins) # To get the data into our environment

You should now see the penguins object in your environment page. Go ahead and click on it to see it in the viewer and look around.

2. Numeric Summaries

We’ll start our exploration by using the str() function on our penguins dataframe. This will gives us the number of cases (rows) and variables (columns) in our dataframe, and tell us the types of our variables.

To get some more details, we will use the skimr package. We installed it during install day, so all we need to so is load it using:

library(skimr)

After that, we are set to skim() our data. Try running skim(penguins).

The skim() function gives us a bit more information than str(), and even some miniature visualizations! Let’s look through the output and digest some of it. At the top is a “Data Summary” which provides much the same information as str(), we have the number of rows and columns, plus the number of columns with specific data types.

The bottom portion of the skim() output provides information on the variables, separated by their type. First you will see factor variables, which we have discussed but never encountered. Factors are meant for categorical data, with the option of those categories being ordered. A plain old category is essentially and way to describe something, in the case of our penguins, an example is the island they were found on. You could have an ordered factor if there was a clear hierarchy of categories, for example months could be categories, with a clear order of January first to December last.

The numeric variables are also shown, along with some important numbers such as their mean and standard deviation. Something shared between both variables types is the n_missing, or “number missing.” This lets us know how many NAs are in the variable column.

How many missing values are there in the bill_length_mm variable?

2 NAs

If we wanted to get some information about one particular column in our data, we could also use the summary() function. summary() is a very versatile function in R, whose behavior changes depending on what you give it as an argument. For now, let’s try it on a numeric vector like penguins$bill_depth_mm using summary(penguins$bill_depth_mm). The result is called a “five-number summary” (even though there are six numbers here).

The five-number summary includes the following (and the mean, because it’s useful): * The minimum value in the vector * The first quartile (25% of the data falls below this value) * The mean and median (50% of the data falls below this value) * The 3rd quartile (75% of the data falls below this value) * and the max.

These five numbers give us a sense of how what the spread of the data is, and can clue us in to potential outliers later. It helpfully also tells us how many values are NAs!

Use summary() on the flipper_length_mm column. What is the 1st quartile?

summary(penguins$flipper_length_mm)

3. Tables

The table() function is a super simple yet effective way of understanding your data set. It simply counts how many of each category exists in your data, and reports that back to you. For example, if you run:

table(penguins$island)

It will tell you how many of our cases (rows) appeared on each island in the data set. You can also pass along two different categories to find out how many cases fir in to two categories at once. For example try:

table(penguins$island, penguins$species)

What is the resulting table telling us? Explain what the 0s in this table mean.

This table shows how many penguins of each species were seen on each island. The 0s mean there were no penguins of that type seen on those islands.

4. Plots! Plots! Plots!

Bar Plot

A bar plot is most often used to show the frequency of categorical data, or how many times do things of this category show up in the data set? In this case, we will be plotting the frequency of each category of penguin in our dataset. We have three species of penguins in our data, the Adelle, Chinstrap, and Gentoo penguins. Try using the following:

barplot(table(penguins$species))

Here our barplot shows the species of penguins on the X (horizontal) axis, and the frequency on the Y (vertical) axis. So from a glance, you can see there are about 130-ish Gentoo penguins in the data. You’ll notice that we actually used two functions here, one inside the other. This is the same as doing:

pengi_table = table(penguins$species)

barplot(pengi_table)

Both are valid options, but it’s usually not a good idea to layer too many functions inside one another.

This question may be tricky. Why do we need to give barplot() the output from table(penguins$species), rather than just penguins$species? Check the help file for barplot() using ?.

This table shows how many penguins of each species were seen on each island. The 0s mean there were no penguins of that type seen on those islands.

Histogram

Histograms are like bar plots, but for variables that are continuous, meaning there are no boundaries between them; this pretty much always means numeric data. Where barplots look at distinct categories, histograms look at numbers. Make a histogram of the body_mass_g variable using hist(penguins$body_mass_g).

Here we see the body mass of our penguins on the X axis, and the frequency of how many penguins have about that body mass on the Y axis. There are a few more choices to be made with a histogram, specifically how many bins we want, or how our variable on the X axis will be grouped. We can control this using the breaks argument to hist(). The best way to illustrate this is to try it:

Run the following three commands. What is the difference in the plots they produce?

hist(penguins$body_mass_g, breaks = 10)

hist(penguins$body_mass_g, breaks = 50)

hist(penguins$body_mass_g, breaks = 5)

The number of breaks determines the number of bins. More bins seperate the body mass into smaller categories for plotting.

Scatter Plot

A scatter plot is used to look at two continuous variables and compare them to each other, often to look for relationships. One relationship that may make sense in between body_mass_g and bill_length_mm; in other words, do larger penguins have longer bills? We can find out using the following:

plot(penguins$bill_length_mm, penguins$body_mass_g)

Here we see bill_length_mm on the X axis, and body_mass_g on the Y axis. Each dot in the plot is once case in our data. Unlike other plots, the Y axis here is not frequency, but instead another continuous variable.

Make a scatter plot looking at the relationship between body_mass_g and flipper_length_mm.

plot(penguins$flipper_length_mm, penguins$body_mass_g)

Line Plot

Line plots often look at change over time in a variable. You’ve most likely seen these before, especially on the news. Line plots are like scatter plots, but the points are connected. Unlike the other plots, we need to do some pre-processing to make a line plot.

Let’s say we want to look at the mean body mass of all penguins over time. We want years on the X axis, and mean body mass of penguins on the Y. To do this, let’s make a new data frame containing a column for year, and a column for mean body mass:

line_data = data.frame("year" = c(2007, 2008, 2009),

"mean_mass" = c(

mean(penguins[penguins$year == 2007, "body_mass_g"], na.rm = TRUE),

mean(penguins[penguins$year == 2008, "body_mass_g"], na.rm = TRUE),

mean(penguins[penguins$year == 2009, "body_mass_g"], na.rm = TRUE)

))

We can then use our new data frame to make a line plot (giving the type = "l" argument to say we want a line):

plot(line_data, type = "l")

Seems 2008 was a good year for penguins! Plots like this are important for monitoring the health of an animal population over time. If there was a steady downward trend in penguin mass, we may be concerned they aren’t getting all the food they need. Later on we will make more complex plots where we can see the trends for each species of penguin.

Box Plot

The last of the big five plot types is the box plot. The box plot is essentially a visual representation of the five-number summary we get from summary(). You can make a boxplot using the boxplot() function. Let’s test it out with both of the following:

summary(penguins$bill_depth_mm)

boxplot(penguins$bill_depth_mm)

Compare the results of summary() and boxplot() above. How do each of the components of a box plot align with the five-number summary (the mean isn’t plotted).